The future of Cyber-Archaeology

Gaming and Augmented Reality

About

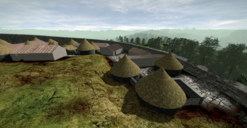

During the first decade of 2000, roughly a million people turned to 'Second Life' to experience the 3D alternative reality. This included some archaeologists, who sought the opportunity to expand their post-processual studies. In short, users could interact with each other and create new versions of human societies on that platform. By the time Dr. Nick Bostrom first published his simulation argument in 2003, many stated that virtual worlds would be experienced through virtual reality interfaces so powerful that the virtual would be indistinguishable from the real. The virtual characters (avatars) are tokens that represents us and we will assign meanings to the world we interact with through them: something from the symbolic. In this new form of transhumanism, time paradox, we teleport ourselves to a simulation of the past. The outcome psychometry from our scientific contact with the (re)constructed sites should then be used to question our archaeological readings and achieve new answers for certain paradigms that cannot be tested otherwise. To think of our perception between contemporary time and the archaeological simulation is a desired process for this transmogrification, especially if we do it collectively.

Death in the Mist - A Cyberarchaeological Archieve of Metanarratives (2022)

Built during the Cold War, the contemporary global village has metanarratives that support its own reality. Breaking the fabric of time and space, the author positions himself between the 60s and 80s of the 20th century, exposing its political-social context that will be theatrical and performative, continuous to the present day. Explores an archive of some of the metanarratives that came to influence the construction of the proto-historical narrative for the northern region of Portugal. Thus, he explores different interdisciplinary concepts that will help him in his cyberarchaeological excavation and simulation. He also ponders the role of computer piracy for the disruption of the so-called 'tyrannies of the image' and its metanarratives for a standardization of ideas and sites. Faced with an economic network of tourism that was fictionalized by the West, he questions the idea of institutionalizing the archaeological heritage as a vehicle for the maintenance of historical-culturalist paradigms that are, in themselves, archaeological records in the 21st century.

Archaeology and Simulation: Contribution to a Debate about Reality (2021)

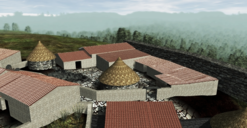

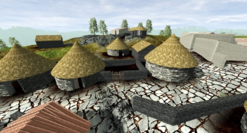

The so-called “Digital Era” has been marked by the creation of simulated worlds in videogames where anything is possible. As technology progresses, so does the veracity of these same virtual worlds. It is increasingly believed that games will one day be indistinguishable from reality, providing immersive experiences with avatars similar to humans themselves. Faced with this reality, there are those who question whether it is possible for us to be the equivalent of a game from any other reality. But it is important for us to debate, from an archaeological point of view, the type of experience that researchers can have in a virtually (re)constructed past and the meaning of reality - whether virtual or imaginary.

Essay on Archaeological (Re)construction as Performance (2020)

This essay aims to explore, albeit timidly, the creative potential of archaeologists in their search for the past. The author tries to establish connections between “being now” and “being then” – the fundamental dynamics for a theatre of archaeological (re)construction, reflecting on the relationships between actor (archaeologist) and witness (archaeological record), being aware of ephemeral and mediation practices and concepts. That is to say, the author examines notions and processes of belonging for the performance of (re)building a past that is simultaneously contemporary.

Quotes

The best reading references

"What used to be the sole province of printed fiction, which offered a univocal entry point to imagined spaces, we now have fully realized, interactive, digital built environments to help us create our own stories within the context of these new, virtual worlds."

"Occuring in relation to situated acts, 'presence' not only invites consideration of individual experience, perception and consciousness, but also directs attention outside the self into the social and the spatial, toward the enactment of 'co-presence' as well as perceptions and habitations of place."

"Notions of the archaeological, sociological, and geographical imagination all imply creative understanding of life today, of possibilities of change, innovation, of the roles of individual perception, practice and agency."

Get Inspired

Selected Videos

Join In

Follow on social networks